The Dissent of a 90-Year-Old

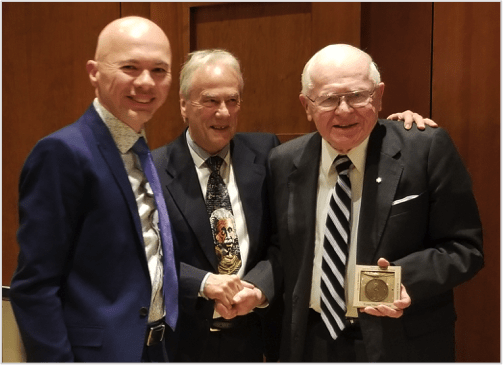

Address by Hon. Douglas Roche, O.C. Presentation of Sean MacBride Peace Prize Toronto, April 25, 2019

“A 90-year-old man appears before you, sighing not for the past but crying for the future. It is not my lost youth that I pine for but a lost future for my grandchildren and their children. Nuclear weapons and climate change threaten their very existence. I dissent from public policies today that will lead to their world being blown up or burned up.

Much of my public career, which started nearly a half-century ago, has been marked by dissent, and I’m not stopping my protest now. I dissent from the anti-humanitarian policies of war for peace. I dissent from the perpetuation of poverty through the greed of the rich. I dissent from the despoliation of the planet by short-sighted industrialism. Most of all, I dissent from the fabric of lies spun by the proponents of nuclear weapons who would have us believe that these heinous instruments of mass murder make us safer.

Governments go on pretending that the military doctrine of nuclear deterrence will bring security and that the half measures of a carbon tax will curb global warming. But these policies are failing. We are in a climate emergency and continued global warming threatens to make huge areas of earth uninhabitable. Likewise, a new nuclear arms race is underway and the current modernization of the 15,000 nuclear weapons held by nine states increases the chances of a nuclear war that would wreck the environment and trigger global famine.

It is not hard to predict that nuclear weapons will one day be used if they continue to proliferate among countries, to foresee rising terrorism that exploits discrimination and inhuman living conditions, to anticipate that rising temperatures and waters will forces the dislocation of millions of people who will swamp already overcrowded systems.

These threats to humanity ought to spark outrage, for they are caused by human folly.

We in Canada, this land blessed beyond belief with natural resources of land, minerals, forests and water, bear a special responsibility in building humane global policies. We used to be a world leader in implementing the broad U.N. agenda for peace. Now our silence is deafening.

It isn’t that globalization is just too much for us to figure out, that we lack the brainpower or international instruments to bring stability to the world in the midst of change. Far from it. We have immense stores of knowledge and, in the United Nations, the essential machinery to address the problems of armaments, poverty, pollution, and human rights violations. But the captains of our society — the politicians, the diplomats, the media and the corporate structures — cannot, do not, will not, all to varying degrees, lift up their vision and work together to make Canada a driver in preserving the world as a fitting habitat for all humanity.

I want a world that is human-centred and genuinely democratic, a world that builds and protects peace, equality, justice and development. I want a world in which human security as envisioned in the principles of the U.N. Charter, replaces armaments, violent conflict and wars. I want a world in which everyone lives in a clean environment with a fair distribution of the earth’s resources. and international law protects human rights.

Since governments have shown that they cannot muster the political will to build true human security, civil society must step in. In fact, it is the leading edge of civil society that is today advancing the ideas of nonviolence that are at the core of the human right to peace. In the great world transformation we are living through — moving from a culture of war to a culture of peace —the real creativity is found in civil society movements. The International Peace Bureau, the Pugwash movement, Public Response and Peace Magazine, all represented here tonight, provide us with the hope we need to go on working for peace.

I have found that, for me, personal creativity is the best way to express my dissent. The two groups that I have led, Parliamentarians for Global Action and the Middle Powers Initiative, provided outlets for me to inject energy into the political systems. Dissent can become creative when we care enough about failed public policies to do something to move forward. Out of our griefs and anxieties, we build a new basis of hope.

What I feel most is that the human journey cannot be stopped. We are often, in spite of ourselves, raising up our civilization. An alliance of civilizations lies ahead — if we can avoid blowing up or burning up the earth. The photograph of Earth taken from space by the astronauts reveals our wholeness and, street fighting notwithstanding, our unity as a human family. Our vulnerability is apparent, but so is our strength — in knowledge, technology and creativity.

I suppose I won’t see the world of my dreams. Time is running out for me. But I am not unhappy about that. I have had a marvellous life and I know how blessed I am. To have had such opportunities as a journalist, educator, Member of Parliament, ambassador and senator is a rare privilege. To have participated in the struggles of our time to advance human security has developed me as a person. To have been sustained by the love and support of my family has enriched me in countless ways.

Even though I am often in dissent at the news of the day, I am at peace with the world, and I think I have found peace within myself. This is perhaps another paradox, like the world going in two directions at the same time. Because I want peace in the world so much, I feel it, and this, in turn, makes me want to keep working for it. I could not stand up and lecture about peace or write books about it if I did not feel peace within me. The words of the prophet Isaiah guide me: “Peace, peace to the far and near, says the Lord, and I will guide them.”

Though relinquishing positions of responsibility, I’ll go on working for peace until God decides otherwise. The grandstand has no appeal for me. I’ll never quit this work. There’s too much to do.”