15 May 2024 | Rome, Italy | Executive Director Sean Conner

“We are now at an inflection point. The post-cold war period is over. A transition is under way to a new global order. While its contours remain to be defined, leaders around the world have referred to multipolarity as one of its defining traits. In this moment of transition, power dynamics have become increasingly fragmented as new poles of influence emerge, new economic blocs form and axes of contestation are redefined. There is greater competition among major powers and a loss of trust between the global North and South. A number of States increasingly seek to enhance their strategic independence, while trying to manoeuvre across existing dividing lines.”

– Antonio Guterres in the New Agenda for Peace

- After the second war in particular, there was a change in understanding that issues of peace and security around the world are inextricably linked – that threats in any part of the world can have global repercussions. In the post-cold war era of globalization, aided by new technologies, integrated global markets, and ease of travel and communication, this has become increasingly true.

- From this realization rose the United Nations, tasked with the maintenance of international peace and security, the promotion of well-being of peoples of the world, and international cooperation. Yet it seems we’re as far as ever from reaching these intended purposes.

- The G7 Italy 2024 foreign ministers’ statement on addressing global challenges and fostering partnerships acknowledges a commitment to upholding the humanitarian and international law, including the UN Charter and human rights and dignity for all. It acknowledges the need for collective action to preserve peace and stability and to address global challenges – climate change, pollution, biodiversity loss, global health, education, gender inequality, food insecurity, violent extremism and terrorism, information integrity and a digital transition. The G7 is committed to the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development and meeting the SDGs and blames Covid and ongoing major conflicts as preventing their achievement.

- While encouraging to read these commitments, the same commitments year after year have not produced the desired results.

- New conflicts are breaking out, old conflicts are never resolved. Let’s look at a couple recent examples:

– Libya: destabilized by a NATO military intervention in 2011 – 13 years on, the instability continues and G7 ‘continues to help Libya put an end to its protracted internecine conflict’.

– Ukraine: despite billions of dollars of weapons transfers and sales to Ukraine, the war drags on with no sign of ending.

– Gaza: several countries of the G7 lead the way in weapons transfers to Israel which have resulted in 34,000 Gazans dead and the violence continues.

– From the Horn of Africa to Sudan to the DRC, Myanmar, South China Sea – the approaches simply are not working.

- Why you may ask? There are certainly a multitude of reasons and no one can fully explain everything – but doing the same thing and expecting different results is the definition of insanity. So let’s look at a few points of what is being done now:

– The G7 consistently highlights working with partners – mentioned 40 times in the 2024 Foreign Ministers’ declaration. While seemingly this is good, as it involves more state in looking for solutions, what this actually does is polarize the international community, creating an ‘us vs. them’ understanding of the geopolitical landscape, especially when simultaneously naming and shaming ‘bad actors’ or seeking to win influence over a specific country. It exacerbates global polarization and deeply impacts the future world order, setting the world up for a new cold war.

- Instead, we need a new push for global cooperation – even those who we disagree with – and to work together to address global challenges, finding compromise and balance. That is the basis of diplomacy and conflict resolution.

- The alternative is to increase tensions toward military confrontation with adversaries. This has been the status quo of the G7 and Western governments, whose doctrines based on ‘peace through strength’ and provocative military exercises and alliances have done little to resolve neither violent conflicts nor the vast array of non-violent threats addressed by the G7 such as climate change, global health emergencies, global inequality, and beyond.

- On one hand, the return to great power competition risks complete nuclear annihilation, as is already on display with Russia’s War of Aggression in Ukraine. Whether or not there are active rhetorical threats of their usage, as long as nuclear weapons exist, there will always be a threat of their purposeful or accidental use, and the consequences will surely be devastating and global.

- The G7 also spends 1.232 trillion US dollars collectively between its members, not including the European Union. This is over half of the global total of 2.443 trillion, yet only 7 countries. An arms race is well underway, including in new weapons technologies from autonomous weapons systems to unmanned aerial vehicles or drones, and new space technologies. Technologies that remain un- or under-regulated and pose vast ethical concerns – and contribute to new and alarming risks around nuclear early warning and command and control systems.

- This vast pace of militarization siphons funding for the promises the G7 has made for climate adaptation and loss and damage for the most effected countries – all while the G7 make up the bulk of historic polluters. We must also note that a recent report by Scientists for Global Responsibility and the Conflict and Environmental Observatory estimates that militaries across the globe account for 5.5% of all carbon emissions.

- Climate Collateral Report (2022) – TNI, Tipping Point North South, Stop Wapenhandel

– The richest countries (categorised as Annex II in the UN climate talks) are spending 30 times as much on their armed forces as they spend on providing climate finance

- The SDGs are in desperate need of a rescue plan – The UN has estimated that the world will need to spend between US$3 trillion and US$5 trillion annually to meet the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) by 2030. If the G7 is committed to the SDG, they must prove it.

- So what can be done differently?

- If global security is interlinked, global solutions must also be. That is the fundamental basis of the concept of common security – no state or bloc of states can be secure at the expense of other states. Rivalries between states must be managed, and a spirit of cooperation must lead the way.

- Common security is based on six principles:

- A focus on the individual and human security

- Trust between nations and peoples

- Disarmament and nuclear abolition

- Global and regional cooperation

- Dialogue, confidence prevention and confidence-building measures

- International law, regulation, and responsible governance

- Taking into account the changing world order, this is more important than ever – new fractures, divides, and tensions will exacerbate existing conflicts and increase the risk of new ones.

- First and foremost, the C7 must ensure the universality and impartiality of international law and institutions. There is a strong and to a large degree justified sentiment in most of the world that the rich countries of the Western world and in particular the G7 have enjoyed and benefitted the greatest from international institutions and have not been held to the same standard as others under international law. If the G7 truly supports a ‘rules-based international order’, they must prove this through their own actions and through good-faith reforms for more equitable international institutions. This necessarily requires reforms to global governance at large.

- Furthermore, the presence of nuclear weapons creates an inherent global imbalance that can only be overcome through their elimination. The Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty’s article 6 reads: Each of the Parties to the Treaty undertakes to pursue negotiations in good faith on effective measures relating to cessation of the nuclear arms race at an early date and to nuclear disarmament, and on a treaty on general and complete disarmament under strict and effective international control.

- The global divide is further illustrated by the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons, which the G7 fails to recognize, let alone sign and ratify. The treaty is primarily supported by the global south and shows how these inequalities and power imbalances caused by a few countries and imposed on the rest.

- Of course given that the G7 alone are not the only possessors of nuclear weapons or other weapons of mass destruction, we understand if there are some concerns – but this means actively working with adversaries on nuclear issues and finding common ground. This was possible even during the Cold War confrontation, yet today only new New START treaty remains… it is time to commit to complete nuclear disarmament and in the process build trust between adversaries.

- Emerging military technologies must likewise be regulated on an international level as soon as possible – and with equal application to all.

- Trust is another essential component to common security. A lack of trust creates feelings of mutual insecurity between adversary countries which can lead to a vicious circle of mistrust and escalation of tensions. The G7 must work actively to build mechanisms and institutions that can strengthen trust between nations. Reduced military expenditure, forums for exchange and communication, transparency, and cooperation on points of common concern such as combatting climate change can enhance trust.

- This also means moving away from a ‘military-first’ response to global threats. Since the end of the Cold War, diplomacy has consistently taken a back seat to military intervention – from conflict and combatting terrorism, to responses to climate emergencies and climate change. We must double efforts led by diplomacy to solve the world’s crises and cease the expansion of military responses. As the saying goes, “If the only tool you have is a hammer, you tend to see every problem as a nail.” – it’s time we pick up the other tools.

- This also requires the G7 to recognize the root causes of conflicts and create holistic responses, including economic inequalities and historical injustices and exploitation. Reducing military spending and investing in communities and peacebuilding initiatives will in many cases produce deeper and more sustainable peace.

- Furthermore, the active involvement of grassroots civil society movements and in particular women and marginalized communities is necessary and proven to create more just and sustainable peaceful solutions.

- Finally, all of the above must be done within a context of meaningful global cooperation. The G7 cannot achieve peace alone, nor working only with partners with whom it has good relations. Honest and sincere efforts must be made to bridge divides and gaps and to listen to the concerns, security or otherwise, of adversaries.

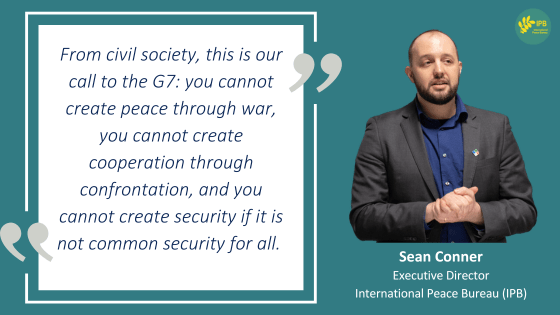

Only when the G7 recognizes that global security is inextricably linked and requires common solutions and cooperation can we move toward peaceful conflict resolution and global justice. From civil society, this is our call to the G7: you cannot create peace through war, you cannot create cooperation through confrontation, and you cannot create security if it is not common security.